| 1.

Probable antecedents include works by Raphael (the now-lost

Judgment of Paris, replicated by Marcantonio Raimondi in an

extant engraving owned by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts); Michelangelo

(figure of Adam in the Sistine Chapel ceiling); and Manet’s

Pastoral Concert (owned by the Musée du Louvre), although

the attribution of that painting is currently in question. |

|

2.

Among the many dependent works are paintings of the same title

by Monet and Cézanne, and paintings by Courbet, Gauguin,

and Matisse. Picasso devoted a series of more than 200 works

in varying media to the Déjeuner. See “Making

Sense of Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” by Paul

Hayes Tucker, Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe,

Cambridge University Press, 1998.

|

|

|

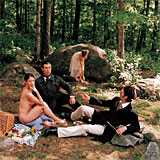

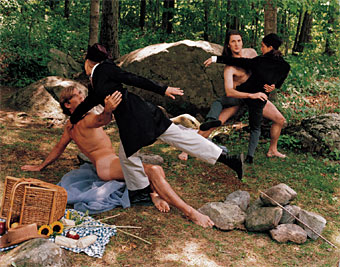

Manet’s

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe is art history’s iconic

picnic: all of classicism leads up to it1; all of modernism leads

away.2 Shocking in its day — which was the mid-nineteenth

century — the Déjeuner has retained its provocative

character all through the years. From the outset, much has been

made about the lone nude figure in the scene. What seems to matter

is not so much that she is naked, but that no one else is. This

leads to a strange imbalance of power, but it is hard to say —

though art critics have made a lot of stabs at it 3 — exactly

how the scales are tipped. Here, in the grand tradition of reinterpretations,

choreographer Jamie Bishton, in league with photographer Tony Rinaldo,

stages his own recensions for 2wice. His is a double translation.

Manet worked in the studio, employing his favorite model, some visiting

relatives, and a painted backdrop. Bishton is outdoors, in the Berkshires.

Manet painted with pigment. Bishton paints with people. Yet Bishton

comes wonderfully and curiously close to the original. (Perhaps

this is because he is a dancer, with a dancer’s casual attitude

towards nudity, which is after all not unlike the attitude of a

studio model.)

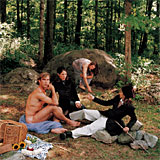

In his most arresting staging, Bishton so marvelously approximates

Victorine Meurent, the naked luncher of the painting, that only

after your first apprehen-sion — that this is the Déjeuner

— do you realize that he has transposed the genders of the

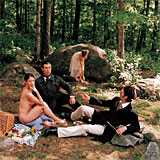

Manet. The choreographer’s more faithful version, though factually

more exact — the women are women, the men are men —

is handsome and correct, but somehow more modest, less compelling.

Why? The exact copy, because it offers up the familiar, the iconic,

lacks the very frisson that made the Déjeuner so strange

and shocking in its day. The flipped version makes the familiar

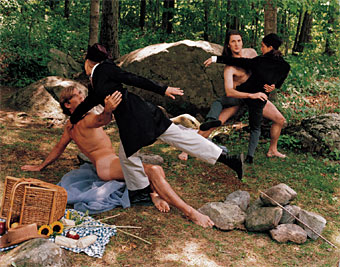

new again. Bishton’s finale, the what-comes-after version,

shows what a lot of people think about when looking at Le Déjeuner

sur l’herbe. Namely, that something risqué or louche

is about to happen, or perhaps already has. But look again at the

naked Bishton and you will see what Manet saw, and know what Manet

knew.4 Under his clear-minded gaze, all things were equal. The naked,

the dressed, the tree,

the picnic basket, the cloth on the ground, the odd piece of fruit

— they are all the same to the artist, who brings all to the

same life, the same stillness. His was the most platonic of lunches

on the grass, a picnic for the sake of art.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

3.

See Bibliography, Tucker, op. cit.

4.

Barbara W.K. Cate, Director, Graduate Program in Musuem Studies,

Seton Hall University, pers. com.

|

|

|

dancers:

Jamie Bishton, Ashleigh Leite, Ana Gonzalez, and Andrew Robinson

|